On Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, Hustle Culture, and Where it All Went Off the Rails Yesterday

There's a Spotify playlist in it for you, but first....

I come to the page today from a position of privilege, so let’s just get that out of the way to begin with. I call myself a “Recovering Corporate Leader,” not because I will never be that again, but because I am one of those lucky souls currently taking time off from the grind – kind of a personal sabbatical without employer sanction. You know, one of those people I used to read about and think, “Lucky bastard. Nice work if you can get it,” while making a face kind of like this (or please reference a nearby mirror to see the expression you’re making. It’s probably similar).

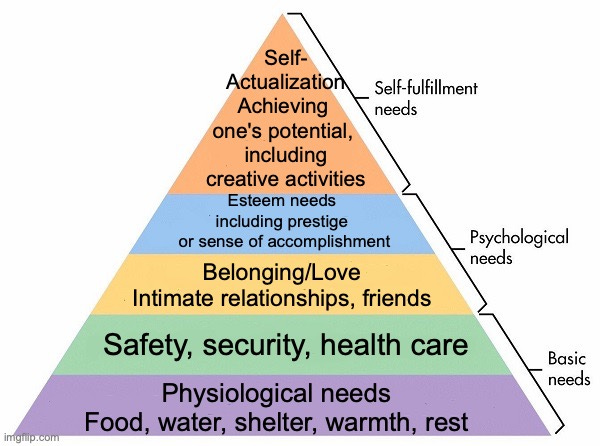

Privilege notwithstanding, the economy and the current state of the world is still a subject of much hand-wringing and clenched-jaw rumination for me. I’m working on a project that has me weighing how much work takes out of us and what living in our fast-paced society costs us on a fundamental level. I was thinking about Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs the other day, and how it seems like we had a few good decades where a significant percentage of people in developed countries felt like they could devote a generous amount of their mental and physical energy toward the top three categories shown here.

I don’t have any data on that; it just seems that way; it’s probably an assumption based on my cis, white history and having grown up in the 80’s, but let’s just run with it.

Lately though, the pandemic, global warming, the vast and exponentially growing disparity between the 1% and the rest of us, armed conflicts, and political polarization have all put what seems to be an out-sized focus on the bottom two tiers of the pyramid. We are back—as a people—to spending most of our time working or worried about paying for food, shelter, and healthcare.

Staying safe, warm, and fed seems to be more and more difficult, despite the fact that we are working more than we ever have since 1940, when the 40-hour work week was established. For the average full-time employee in the United States, that kind of schedule is now more of a unicorn than a standard. According to a 2021 Gallup survey, the average is now 44 hours. The same study indicates that roughly 41% of employees are working 45 hours. 39% are working 50 hours a week, and an astounding 18% are working 60 hours a week. For a large portion of these workers, overtime pay is not provided. Salaried workers, for example, are often considered “exempt” from overtime, so their additional time on the job is donated to the company. American workers have additional burdens compared to workers in other developed countries, such as no mandated vacation time off, no mandated parental leave, no mandated paid sick time, limited power of unions to champion workers’ rights, and rampant layoffs.

For American women, the current day-to-day sensation—anecdotally speaking based on my last couple of decades in the work force and conversations with my friends—is feeling like our hair is on fire. Despite progress in terms of “equity” in the workplace, if you put a general inquiry like “what do women in the United States need” into Google, you get results outlining dozens of necessities still not widely available for us, almost all of which focus on hierarchical needs at the bottom of the pyramid. Nearly all women in the country have concerns at a constant rolling boil about food security, employment equity, fundamental safety, and body autonomy. If these topics are not on the front burner for ourselves, at the very least, they are on a back-burner low-simmer for our loved ones.

Even among the most privileged of us, our employers are making greater demands on our time and energy (in order to keep broadening that economic disparity for the benefit of their owners and stockholders). We may look like we “have it all,” but we are falling into bed at night feeling dissatisfied, alone, disconnected, and wondering if the “all we have” is “all there is.”

My response is not no, but hell no. The Blackfoot Nation, studied by Maslow prior to publishing his ground-breaking theory, flipped the pyramid upside down. For them, self-actualization (most commonly demonstrated through generosity) was considered the most fundamental necessity, not a fluffy “nice to have.” The focus on the good of the community and practice of spirituality resulted in everyone in the community being provided for, and hence, the physiological safety of everyone took care of itself. I believe, as the Blackfoot Nation did, that fulfilling higher level needs will result in the rest of our needs being more consciously and joyfully met. It sounds like I am foisting some kind of leftist liberal agenda on you but hear me out. Whenever we are tackling a societal or personal problem and we insist on continuing to do the same thing we’ve been doing, we need to pause and answer the old Dr. Phil question: “How’s that working out for ya?”

Working more for employers who show increasingly callous regard for their work force doesn’t seem to be the answer. The pay isn’t keeping pace: the American Dream is slipping through the grasp of so many of us. Even if the pay secures what we need, working more is making us insane, and leaving so little room for the good stuff: the self-actualization, the creativity, the connection.

There’s an assumption that speed and productivity lead to success, which leads to happiness, but there’s a growing body of evidence that indicates it’s really a happiness-first equation. Daniel Pink argues in Drive: The Surprising Truth About What Motivates Us that human motivation is primarily intrinsic. We are driven to meet goals that satisfy our internal desires for autonomy, mastery, and purpose. Shawn Achor wrote The Happiness Advantage: The Seven Principles of Positive Psychology That Fuel Success and Performance at Work based on his assertion that happiness fuels success, not the other way around.

As a former leader in the fast-paced insurance industry, I can attest that racing the clock to do more faster just led to readjusted goals requiring even more and even faster. Not once did I have an employee reach out to me to tell me how happy they were because they achieved a productivity goal established by some big wig in Boston or New York. But I did have already happy employees make significant contributions to the department, meeting objectives they created for themselves that focused on mastering a topic or process or by finding ways to deepen the ties between their values and purpose to the work they did each day.

You can tell your employees to work harder, faster, smarter, and more. You can hold them accountable if they don’t. But I’ll tell you two things. 1. If you do, it will feel like shit. I spent years doing that, and it felt like shit. Every night, I went to bed with my company’s expectations weighing on my mind, and every morning, I woke up thinking about my team. What could I tell them today that might inspire them to meet those objectives (many of which seemed arbitrary)? 2. You can be the hard-ass asking for more, faster, but what you won’t be doing is fostering connection, company loyalty, employee satisfaction, internal referral rates, or creating an environment where the employee feels empowered and enabled to contribute their best work and best ideas.

The same goes for our personal lives. If your goal is just to run a seven-minute mile, what does that lead to? A new goal for a 6:45 minute mile? If, however, your goal is to deepen your mindfulness, breathing, focus, and improve your running form, what will that lead to? I’m not a runner anymore, and I was never that fast, but my guess is that focusing on the happiness aspects of the run will, as a consequence, yield deeper success in the run and more commitment to continuing to run, which will probably lead to that seven-minute mile.

Let’s use another example that even more clearly illustrates my point: If the goal is to cook, eat, and clean up after dinner in forty-five minutes, what did meeting that goal contribute to your overall happiness quotient at the end of the day? Probably nothing at all; in fact, it was probably a net loss and may have even resulted in some negative feelings between you and your housemates. If, however, your goal was to have a relaxing dinner enjoying the company of your family with food and atmosphere that enhanced your sense of peace, what would meeting that goal contribute to your sense of happiness? And how motivated would you be to be prepared and productive enough to pull such a feat off every evening?

While pondering on these and other related topics, I kept hearing Billy Joel singing Vienna on the constantly playing jukebox in my mind. And this, my friends, is where my day went off the rails.

Slow down, you crazy child

you’re so ambitious for a juvenile

But then if you’re so smart tell me

why are you still so afraid?

Where's the fire, what's the hurry about?

You better cool it off before you burn it out

You got so much to do and only

so many hours in a day

Then, from a couple decades later, I could hear the Eagles implore:

Just another day in paradise

as you stumble to your bed

Give anything to silence

Those voices ringing in your head

You thought you could find happiness

Just over that green hill

You thought you would be satisfied

But you never will

Learn to be still

I started to wonder which other musicians had been telling us to just take a beat, and that of course led to the day’s rabbit hole. And with that, I present a Spotify playlist with over 50 songs from various decades and genres urging us all to find the wisdom of Claude Debussy: “Music is the space between the notes.” Similarly, peace in our lives won’t come from being constantly producing. It is the space between the tasks on our to-do list. I hope you can find a few moments of it today.

I've read this twice ... and each time got Vienna stuck in my head

my heart soars reading your words 🖤

Wonderful! Thank you for posting your take on MHoN!